2011 / Art Mur, Montreal, QC / Sculpture

Mixed Blessing wears the words “FUCKIN INDIAN” and “FUCKIN ARTIST” in the form of a cross. I am both Anishinaabe and artist at once. There is no struggle within; that takes place on the outside.

Rebecca Belmore,

An interview with Rebecca Belmore by Wanda Nanibush, University of Toronto, 2014

Photo credit: Toni Hafkensheid / Jessica Bradley Inc.

2017 / documenta 14, Filopappou Hill, Athens, Greece and Kassel, Germany / Sculpture

Rebecca Belmore has made a monument to the transitory, out of local materials. A tent—increasingly a long-term home for refugees and migrants—has been hand carved in marble. It is a testament to what, for many, is a state of perpetual emergency, a makeshift retreat. The form has its root in other vernacular shelters as well. “The shape of the tent is, for me, reminiscent of the wigwam dwellings that are part of my history as an Indigenous person,” Belmore explains. Wigwams (wiigiwaam in Anishinaabemowin), traditionally constructed of bentwood of young trees and covered with birch bark, are a rather ingenious solution for building with the materials available at hand. They also enabled people who were in constant motion to make their home wherever necessary.

Candice Hopkins,

Rebecca Belmore Showing at documenta 14 in Athens, 2017

Photo credit: Scott Benesiinaabandan

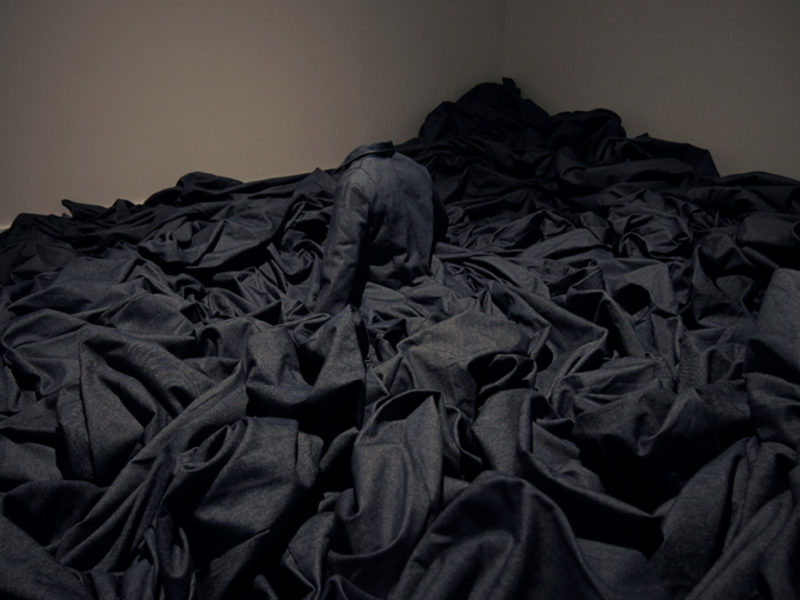

2017 / PLATFORM Centre for Photographic + Digital Arts, Winnipeg, MB / Exhibition

In early July 2017, Rebecca Belmore, Florene Belmore and Scott Benesiinaabandan spent a week together near Sioux Lookout, Ontario. A photo from the Ontario Archives taken by John Macfie in 1955 drew them to the site. In the photograph, taken before the artists were born, seven boys from the nearby Pelican Falls residential school in denim coveralls watch a man fishing.

At Pelican Falls was inspired by this photograph.

Jessica Jacobson-Konefall,

At Pelican Falls: Rebecca Belmore, 2017

Photo credit: John Macfie (archival photo), Ray Fenwick / PLATFORM

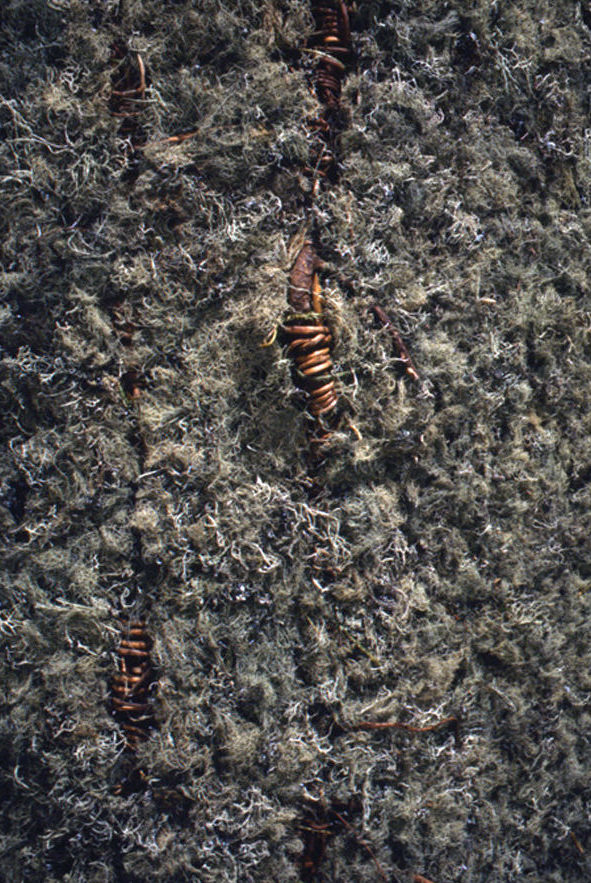

1993 / Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver, BC / Installation

The central component of

Wana-na-wang-ong is comprised of two curved suspended panels, each suggesting the horizontal configuration of a landscape painting. As a primary formal feature, the interwoven spruce roots also provide the supportive framework, or skeleton, for the lichen and peat moss. Suspended from the ceiling, and not touching the floor, the panels float in a space of ambiguity that questions the limitations of such binary oppositions as permanence/ impermanence; life/death; survival/resistance; positive/negative; inside/outside; art/craft. This “magical state of suspension” celebrates Belmore’s freedom from the strict confines of these notions, and metaphorically alludes to the dynamic energies of oppositional forces implied in the tensions and balances of life.

Lee-Ann Martin,

The Language of Place, Contemporary Art Gallery, 1993

Photo credit: Robert Keziere / Contemporary Art Gallery

1996 / The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery, Toronto, ON / Installation

A gigantic inclined plane stands covered in plastic milk bags filled with water taken from Lake Ontario. At its foot, a functioning drinking fountain promises fresh water, while at its head a longish staircase leads to a small platform fitted with a very small telescope. Looking through it, the viewer can see the great rolling waves of the lake, up close.

Temple brings us face to face with the utter simplicity of water, its being-there-ness and its intrinsic necessity. To do so it uses the closest available water source, so densely polluted it must be treated at a facility down the road from the gallery before it can be consumed.

Marilyn Burgess,

The Imagined Geographies of Rebecca Belmore, Parachute 93, Jan/Feb/Mar 1999

Photo credit: Cheryl O’Brien / The Power Plant

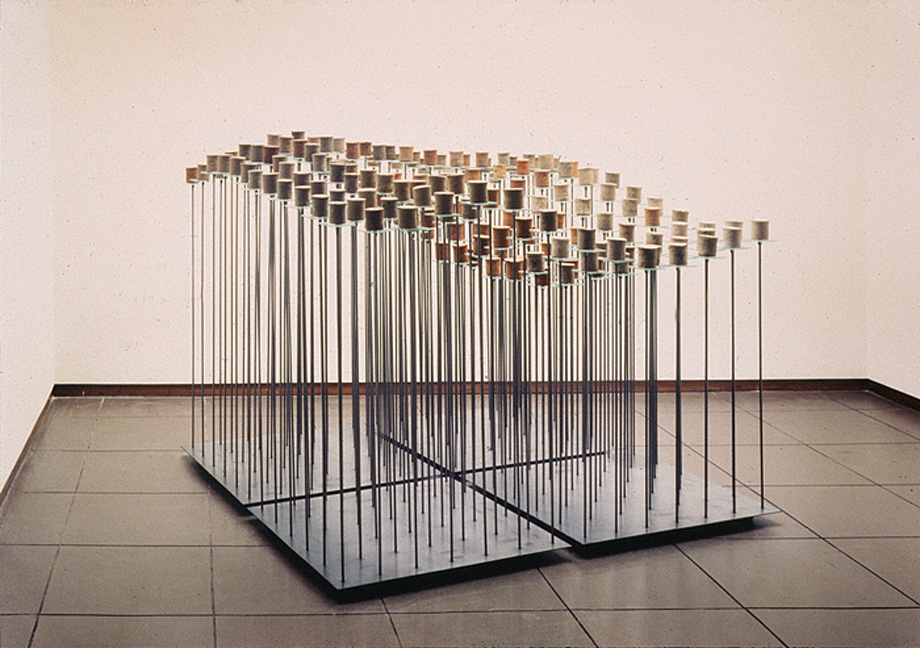

1995 / SITE Santa Fe, NM / Installation

Belmore drove from Sioux Lookout to Santa Fe taking a long route through thirteen states, collecting soil samples and souvenir cups along the way to map the journey. One of the stops was Oklahoma City, where the federal building had been bombed a few months earlier: [as Belmore described] “The building had been taken down… There was a chain link fence inside of which they were cleaning up the rubble with bulldozers. Basically, what was left was just a mound of dirt. While we were there as tourists, hanging out at the fence, there were other people from all over the U.S. who came to witness. They decorated the fence with poems and teddy-bears. People would talk with each other, express their horror… They were shocked at the violence within. When we got to Santa Fe, I took the soil samples I had collected, formed them in the inside of the cups and sun-dried them, which is how the local people do their adobe. There are 168 of them—which is the number of people who died in the bombing…”

Belmore named the Santa Fe piece

New Wilderness. “The new wilderness that we live in now is, of course, this violence within our own fence, within our own territories.”

Debbie O’Rourke,

An Artist in the New Wilderness: Interventions by Rebecca Belmore, Espace, 1997-1998

Photo credit: Robert Keziere / SITE Santa Fe