2003 / Sculpture

In 1823, English furriers captured Demasduit’s niece, Shanawdithit, who lived in St. John’s until her death in 1829 and became legendary as the last of the Beothuk. In

Shanawdithit, The Last of the Beothuk, Belmore commemoratively evokes the woman’s presence (and absence) with haunting stone sculptures of her feet and hands, rounded as if worn by water, sensuously connecting her to the land from which she was taken. These objects also suggest traces of ‘primitive’ culture, the artifact-like qualities echoing the anthropological interest Shanawdithit endured.

Heather Anderson,

Rebecca Belmore: What Is Said and What Is Done, Carleton University Art Gallery in partnership with

National Gallery of Canada’s

Sakahàn: International Indigenous Art, June 2013

Photo credit: Trevor Mills / Vancouver Art Gallery, Justin Wonnacott / CUAG (detail)

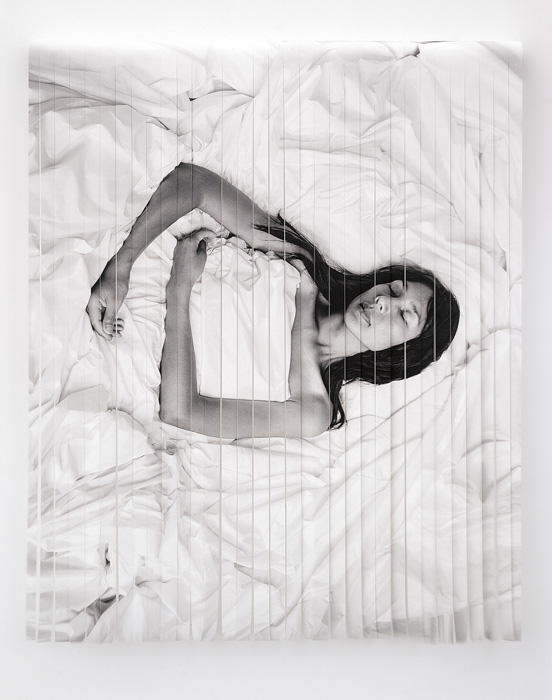

2002 / Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, Vancouver, BC / Photograph

State of Grace depicts a young Indigenous woman slumbering, draped in white cloth that spills around her body. She looks serene, relaxed. Yet the paper on which the photograph is printed has been slashed into vertical strips, suggestive of a latent violence inflicted on her body.

Rupert Nuttle,

Beauty in Difficult Places: the Visual World of Rebecca Belmore, National Gallery of Canada, August 2018

Photo credit: Donna Hagerman, Howard Ursuliak / Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery (installation view)

2002 / Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery / Vancouver, BC / Sculpture

In Belmore’s

The Great Water, a canoe is capsized. In this cloth sculpture made for the exhibition,

The Named and Unnamed, both vessel and surrounding waters are made of, and engulfed in, the same great swathe of black canvas. The emptiness of the canoe’s grey interior is a gaping wound against the rich opacity of black cloth.

Marcia Crosby,

Humble Materials and Powerful Signs: Remembering the Suffering of Others,

Rebecca Belmore: Rising to the Occasion, Vancouver Art Gallery, 2008

Photo credit: Howard Ursuliak / Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery

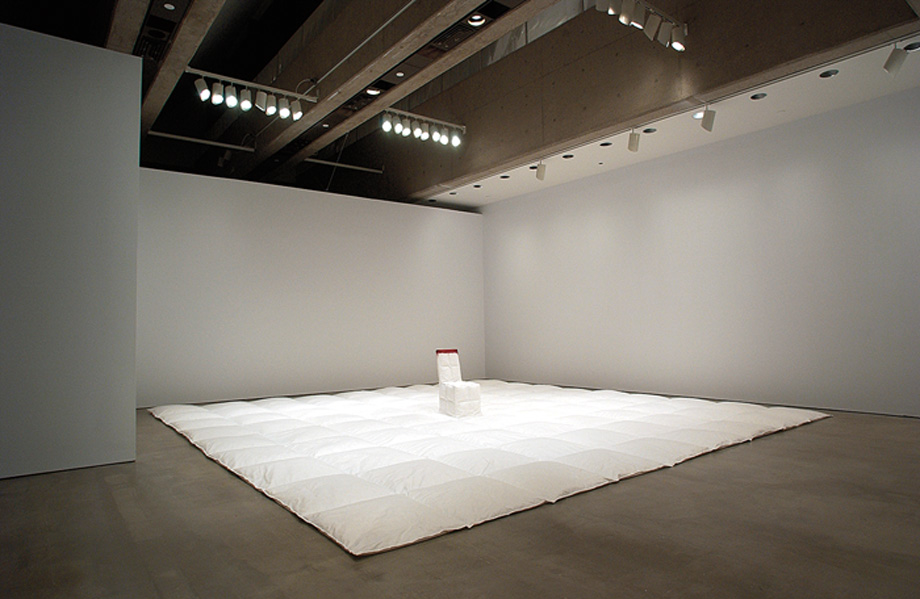

2002 / Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, Vancouver, BC / Sculpture

The 19th-century massacre at Wounded Knee and the 2002 discovery of the remains of dozens of missing women, many of them Aboriginal, at a pig farm outside Vancouver were the subjects of Belmore’s installation

blood on the snow, created in 2002 for the exhibition

The Named and the Unnamed, organized by the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery. The work, which toured Canada with the show, presents a pristine white blanket of snow defiled by the blood of the dispossessed. Blood running down a white chair at the centre of the blanket seems to stand for pain and violence in the midst of cold, white indifference. For Belmore, it is an extension of ongoing violence against Aboriginal people.

Lee-Ann Martin,

The Waters of Venice: Rebecca Belmore at the 51st Biennale, Canadian Art, June 2005

Photo credit: Art Gallery of Ontario

2008 / The Rooms Provincial Art Gallery, Newfoundland and Labrador / Video installation

Belmore’s work often starts in the performative and in

March 5, 1819 she shows us the trauma inherent in the pursuit and murder of a man and the capture of his wife. The work isn’t about memory or history but about disruption and disappearance. For Belmore, there is no one left to remember. The writing of history hasn’t evoked their reality but rather stands in for them as an absence. The history doesn’t tell us of two people in love, just starting a family, in a harsh physical environment made harsher by the coming of the colonialists.

Glenn Alteen,

Rebecca Belmore – March 5, 1819, 2008

Video credit: Noam Gonick

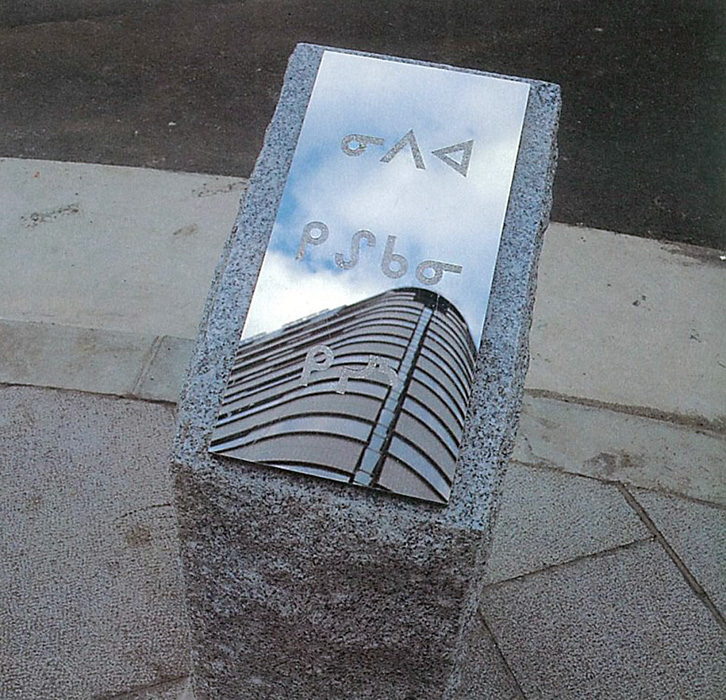

1994 / Faret Tachikawa Art Project, Art Front Gallery, Tokyo, Japan / Public Art

I Wait for the Sun is an outdoor text-based work that reads: “I Wait for the Sun” in Anishinaabemowin syllabics and in Japanese. It is made of two steel plates, one with a highly reflective surface and the other is non-reflective. The reflective plate is engraved with Anishinaabemowin and angled to face the non-reflective plate mounted on the wall. The non-reflective plate is engraved with the Japanese translation of the text. When the sun illuminates the face of the Anishinaabemowin plate it reflects the sunlight onto the Japanese plate.

Photo credit: Art Front Gallery

2005 / Canadian Pavilion, Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy / Video installation

Fountain [is a single-channel video projected onto falling water that] deals with elementals or essences: fire + water = blood. The time is both now, in the industrialized landscape of North America, and in another zone, a time of creation, myth and prophecy. The element of water is represented both as a body of water in the projection and literally as a wall of falling water. Water turns to blood. As befits our times we do not know whether this is a metaphor for creation or an apocalyptic vision.

Jann Bailey and Scott Watson, eds.,

Rebecca Belmore: Fountain, coproduction of Kamloops Art Gallery and Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery, 2005

Video credit: Noam Gonick

Photo credit: José Ramón González (production stills / installation view)

1994 / 6th Native American Fine Arts Invitational, The Heard Museum, Phoenix, AZ / Sculpture

Thousands of pine needles that glimmered red and gold were inserted through wire mesh stretched in rectangular frames in homage to a homeless woman who froze to death on the streets of Sioux Lookout, Ontario, near Belmore’s home. The work recalls the harsh circumstances of a woman’s death juxtaposed against the severity of nature. It was created with Belmore’s characteristically intense and repetitive gesture, meticulous and exhausting, perhaps as an act of perseverance against the injustices of contemporary society.

Daina Augaitis and Kathleen Ritter, eds.,

Rebecca Belmore: Rising to the Occasion, Vancouver Art Gallery, 2008

Photo credit: Trevor Mills / Vancouver Art Gallery

1991 / Various locations in Canada and USA / Sculpture

A two-metre-wide wooden megaphone carried by a procession of about sixty people to a mountain meadow in Banff National Park. Participants erect the megaphone so that the voice of those speaking echoes up to nine times. This gathering of invited Aboriginal leaders, activists and poets begins with the artist, who is followed by the others who speak to and about the land.

Daina Augaitis and Kathleen Ritter, eds.,

Rebecca Belmore: Rising to the Occasion, Vancouver Art Gallery, 2008

Photo credit: Monte Greenshields / Walter Phillips Gallery, Michael Beynon

1992 / National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, ON / Installation

If there was, as [Robert] Houle claims, a negotiation about identity going on in most of the works in the exhibition, nowhere was that more movingly enacted than in Rebecca Belmore’s work,

Mawu-che-hitoowin: A Gathering of People for Any Purpose. On a plywood floor, partly laid with bits of old patterned linoleum, sat a circle of chairs, all of them different, all of them worn with use. The chairs fitted with audio tapes: the viewer was invited to sit in the chairs and use headphones to hear the voices and stories of the seven different women who had donated them, each one telling of her own experiences. (One recording was of bird song.) This work’s power depended upon the voices and stories of loved ones, community, children and parents. It was a political gesture for Belmore to feature those voices in the space allocated to her art. Here it was perfectly clear that narrative, identity and subjectivity are not just abstract issues, but concrete ones, tied to life.

Scott Watson,

Whose Nation?, Canadian Art, Spring 1993

Photo credit: Louis Joncas / National Gallery of Canada